Emily doesn't really like math. She'll tell you that right to your face if you ask her. Not in a confrontational or disrespectful way; that's not her nature. But with a scrunched up half- frown and shoulder shrug, and a nearly imperceptible shake of the head, she'll say, quietly, almost apologetically, "No, not really."

I watch her walk into class every day. She's tall for a fifth grader, but when she folds herself in at her desk in the back of the room she shrinks down to about half her size, like she's trying to disappear.

Emily's very quiet. She never interrupts. She won't raise her hand. If you call on her she'll respond, but in a whisper you can hardly hear. She doesn't cause any trouble. She follows directions. Her journal is always turned to the right page. She always has a pencil and an eraser. She turns her homework in on time. If you didn't know any better, if you were just a casual observer, you'd think she knows what she's doing because she looks like she knows what she's doing. She's one of those under the radar kids.

I watch her at her desk, elbows flat, head down, pencil up and moving. She appears to be working away. What's she doing? She's managed to get by, doing just well enough to keep one step ahead of the basic skills program. But if you sit down next to her and really, but I mean really try to get at what it is she actually knows, if you look at her work and try to ask her some questions about it, you'll find that her understanding is very superficial. She's doing her best to remember and follow some rules she's been told. She's memorized some things, but they're all fragmented. They don't cohere. She studies for the tests, and does her best to hold the pieces together, but when the tests are over the pieces fall back apart. She doesn't really understand. And despite her best attempts to hide, I know that she knows she doesn't really understand. I think it bothers her, which is why she says she doesn't really like math anyway.

I have to be careful. I can't poke around too much or she'll shrink down even further, away to a place I might not be able to reach. It doesn't take much for me to imagine what math experiences she's had to make her feel this way. I know it's not too late to undo them.

Justin Lanier, in his brilliant, moving Ignite talk The Space Around the Bar, says the following:

"Students Will Be Able To (And Will Never Want To Again.) This is how we can write our lesson objectives if we don't pay attention to how kids feel about math."

Rich and I agree. Rich and I are trying to create a classroom where it's OK to be wrong; where you can ask and answer questions that you yourself have generated and that serve an intellectual need; where you can solve problems in ways that make sense to you, even if it's not the way they want you to do it in the teacher's manual; where tasks have low barriers to entry and high ceilings and open middles and three acts; where you can move around the room and work them out on big whiteboards; where you can collaborate with your classmates, play games, talk, argue, and laugh. We're trying to create that kind of a classroom. We don't always succeed, but we're trying.

Emily's my measuring stick, my benchmark, my litmus test. Whenever Rich and I re-work a lesson, or I get an idea for a task or an activity, I ask myself: What will Emily think? How's she going to react? I want her approval. If I can get her approval I know I'm onto something. The skills and the content are the easy part. If we can create the conditions in class where she feels it's OK to just be herself, to feel safe and secure enough stand up and stretch out to her full height, I know true learning will occur.

When class is ending, I'll find her and ask, "Well, what did you think?" She doesn't give much away. It doesn't always go as well as we thought it would. But sometimes I get a guarded, "Well, that was OK." I'll do a little fist pump, and she'll maybe even smile. Baby steps. Lesson objective: met.

Tuesday, December 13, 2016

Monday, December 5, 2016

Down the Rounding Rabbit Hole

|

| Been there. |

|

| Done that. |

|

| Looks familiar. |

|

| Monkeys? Can't say I've ever tried this, but I'm skeptical. |

|

| Not sure what this is. |

|

| Seems like a lot to process, and I'll admit I've said similar things. |

Our curriculum likes number lines:

|

| Grade 3 |

|

| Grade 3 again. Not a mountain or a roller coaster...it's a hill! |

|

| Grade 4 |

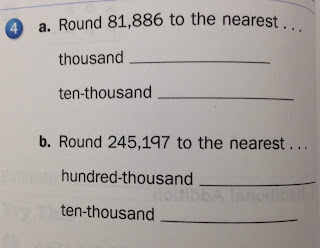

I've spent more time than usual this fall thinking about rounding; both the why and the when, but also simply the how. Using a number line to round is all well and good, but it's not going to help you solve these problems...

...unless you can do the following:

- Identify place value locations and the value of the digit in a given place value.

- Identify the next multiple in that place value.

- Find the halfway point between the two multiples to use as a benchmark.

- Decide whether the number is more or less than halfway.

Last year, I tried something different with some third graders who were having difficulty with rounding. Here's a typical problem from their journal:

|

| An open number line won't help unless you know the multiplies of 10 that come before and after 68. |

|

| Start with 68. |

|

| Count forward by 1s until you get to a number you would say if you skip counted by 10s. |

|

| Same, but this time count backwards. |

|

| Find out if 68 is closer to 60 or 70. This also reinforces complements of 10. |

This was good as far as it went, but to round larger numbers, especially to units represented by a place in the middle of that number, students will need another strategy, hopefully one that doesn't rely on mountains, roller coasters, digits knocking on doors, or monkeys swinging on vines.

This fall I've been working with a fourth grader who, at the beginning of the school year, showed a complete inability to round. She had a very limited notion of place value, and we spent several weeks shoring up some basics.

|

| We used this flip board... |

|

| ...and these place value arrow cards. |

I wanted her to be secure in her knowledge of place value locations and digit values before we ventured off into the world of rounding. It took several weeks, but once she was able to complete tasks like this:

and this:

without the board or the arrow cards, I moved her on to rounding. Here's the plan I had sketched out. Let's take a grade 4 example. Round 81,866 to the nearest thousand:

|

| Step 1: Write the number out in expanded notation. |

|

| Step 2: Identify the place value you want to round to. |

|

| Step 3: Identify the next multiple in that place value. Here I might say something like, "If I was skip counting by thousands, what number would come after 1,000?" |

|

| Step 4: Put the 80,000 back. This can be combined with step 3. |

|

| Step 5: Now we're ready for our number line. We have our two possible responses for rounding 81,866 to the nearest thousand, so now we've got a fighting chance. |

|

| Step 6: Where does 81,866 fall on this number line? Can we benchmark halfway? |

|

| Step 7: This is now a matter of comparing 500 and 866. |

|

| Rounding 697,654 to the nearest thousand. After a while, she started to internalize some of the steps. |

Here's an example of the student employing the strategy in her math notebook:

|

| Rounding 818,325 to the nearest thousand. I would've liked to see her place the mark for 818,325 closer to 818,500, but that's for another day. |

So here's what I found out: 4.NBT.A.3 is a very interesting standard.

|

As I continued to work with the student, the nagging question of why are we doing this kept running through my mind. Curious to learn more, I found this on page 12 of the Numbers and Operations in Base Ten, K-5 progressions document:

Rounding to the unit represented by the leftmost place is typically the sort of estimate that is easiest for students and is often sufficient for practical purposes. Rounding to the unit represented by a place in the middle of a number may be more difficult for students (the surrounding digits are sometimes distracting). Rounding two numbers before computing can take as long as just computing their sum or difference. (emphasis mine)

Here's what I want to know:

- If rounding to the unit represented by the leftmost place is often sufficient for practical purposes, then why are we asking students to round, for example, 287,347 to the nearest hundred? What headache do I have that rounding 287,347 to the nearest hundred will cure?

- Are tasks asking students to round numbers to units represented by places in the middle of a number simply exercises in place value? Is there a way to make this task compelling?

- What distinctions do the progressions make between rounding and estimating?

- Should rounding be taught as a discrete skill, separate from any context?

- What scaffolds, tools, and place value models are helpful in promoting rounding understanding, and which subvert it?

And finally: What are your experiences teaching rounding?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)